|

| ICJ President Joan E. Donaghue reads the 29-page ruling. |

Arrest the Common Sense – it broke the Common Law!

Here’s a quote from James Clavell’s most famous novel:

“The law may upset reason but reason may never upset the law, or our whole society will shred like an old tatami. The law may be used to confound reason, reason must certainly not be used to overthrow the law.”

Many legal scholars fell in love with this adage. What they apparently failed to notice is that Clavell put these ‘wise words’ in the mouth of Yoshi Toranaga – a wily war lord who only pretended to obey the law, while manipulating it to his advantage to make himself Shogun, absolute ruler of medieval Japan.

No, to set the law above reason is to invite fanaticism; to apply a law that confounds reason is to perpetrate injustice.

Laws and the Rule of Law are two of humanity’s most valuable inventions. They can guide us on the road to justice – in the spirit of the biblical injunction צדק צדק תרדף (justice, justice thou shalt pursue).

But, no matter how valuable, every human invention can be used for good or evil purposes. The domestication of animals improved communications, allowed people to ‘delegate’ back-breaking work, reduced famine and filled our innate desire for companionship; but it also provided more destructive ways to make war – war elephants, cavalry charges and horse-drawn cannon. More recently, the discovery of radioactive materials provided a means to save human beings affected by terrible diseases – but also to kill people by the tens of thousands.

Laws are no different: they can be wonderful guardians of life, dignity and freedom; but, throughout history, they were often turned into instruments of oppression. Jews suffered from ‘legal’ persecution even more than they did from lawlessness: think the Inquisition, the Dhimmitude, the Nuremberg Laws, the Soviet show trials… And it’s not always because of bad laws; often it’s about good laws that are twisted to promote hatred and perpetrate persecution. Laws against murder have often been employed in blood libel accusations; those against treason were used to condemn Alfred Dreyfus…

|

| One of Stalin's 'tribunals' delivers its verdict in 1937. 17 people were condemned - some to immediate execution, while others were eventually murdered in 'labour camps'. |

And now an international convention against genocide is being used to reward and succour a genocidal act.

I blame South Africa’s government, of course. But then, there will always be slimy politicians eager to deflect people’s attention from their own woeful mismanagement – by pointing the finger at issues ‘out there’.

All South Africa did was to formulate a ridiculous claim – thousands of pathetic litigators do that each year. In one such case, a plaintiff who choked on a Dorito crisp sued the supplier, arguing that the product was inherently dangerous. After nine years of costly litigation, the claim was finally rejected by the Supreme Court of the State of Pennsylvania, with one judge referring wryly to

“the common sense notion that it is necessary to properly chew hard foodstuffs prior to swallowing.”

Which begs the question: where was the common sense of the judges who allowed that case to proceed and burn through taxpayers’ money for nine tedious years?

A clever lawyer can argue that Doritos are indeed dangerous – by ‘learnedly demonstrating’ that they (‘prima faciae,’ in certain ‘plausible’ ways and all that jazz) tick boxes in legal definitions of ‘potentially harmful products’. S/he might even bring ‘expert witnesses’ ready to swear that people have indeed choked on crisps… But a judge endowed with common sense will rule that Doritos are as much a ‘choking hazard’ as any other tasty snack.

Imagine if the judges would, a few days into those nine years of pointless litigation, ordered ‘provisional measures’ – for instance that the supplier must stop producing Doritos, to prevent the ‘plausible risk’ of people choking on them!

The ICJ judges should have thrown out South Africa’s claim as vexatious; as a politically motivated attempt at ‘legal’ harassment – even more absurd than the Doritos case. That they did not do so is due to a combination of lack of integrity (in the case of some judges) and lack of common sense (for others).

A barrister friend of mine once quipped that judges are interested in law, not justice. The International Court ‘of Justice’ (ICJ) isn’t different in that respect. It seeks to apply what it sees as ‘the Law’. But it shouldn’t do so mechanically, unthinkingly. Justice may be blind, but it shouldn't be brainless. Judges must deliver it without fear and favour, but with fairness. In the absence of integrity and/or common sense, what they’ll deliver is oppression and injustice.

%20(1).jpg) |

| Portrayal of 'Justice': blind, but not batty! |

True, the ICJ took pains to explain that it wasn’t (yet) making a determination on the actual claim of genocide. But it found the ‘risk’ that Israel may commit genocide ‘plausible’ enough to allow the litigation to continue – and to order ‘provisional measures’ aimed at mitigating that ‘risk’!

It did so by suspending common sense and engaging – either deliberately or through fanatic adherence to words over facts – in a box-ticking exercise. It’s all in the 29-page long ruling. Which – unlike the thousands of journalists reporting and the millions of people talking about it – I took the time to read. I also spent my precious time reading the five accompanying documents:

- The Declaration of Judge Xue (China)

- The Dissenting Opinion of Judge Sebutinde (Uganda)

- The Declaration of Judge Bhandari (India)

- The Declaration of Judge Nolte (Germany)

- The Separate Opinion of Judge ad hoc Barak (Israel)

They make for an interesting reading! So let’s analyse the judges ‘reasoning’ – such as it is.

Apparently clear, clearly apparent

The first question that the ruling addresses is that of jurisdiction: does the Court have (at least apparently or ‘prima faciae’) jurisdiction over this case? In order for South Africa to sue Israel, it has to show that there is a “dispute” between the two states “relating to the interpretation, application or fulfilment of the present Convention”. But South Africa is thousands of miles away from Israel. What do they have to quarrel about?

Yet the Court ruled that there was a dispute:

“26. The Court notes that South Africa issued public statements . . . in which it expressed its view that . . . Israel’s actions amounted to violations of its obligations under the Genocide Convention.

. . .

27. The Court notes that Israel dismissed any accusation of genocide in the context of the conflict in Gaza…”

So there you are: South Africa accused and Israel denied, hence there’s a dispute – let’s go to court. According to this ‘logic’, had Israel abstained from denying and just contemptuously held its piece in the face of South Africa’s angry accusations, there would’ve been no dispute and hence no Court jurisdiction over this case. But once Israel denied…

Absurd, I know; but apparently sufficient for this Court to conclude:

“28. In light of the above, the Court considers that the Parties appear to hold clearly opposite views . . . The Court finds that the above-mentioned elements are sufficient at this stage to establish prima facie the existence of a dispute between the Parties…”

The judges must’ve thought long and hard whether “the parties appear to hold clearly opposing views”, or rather ‘clearly hold apparently opposing views’!

Anyway… according to their ‘logic’, if you shout ‘your sister is a whore’ and I respond ‘but I have no sister’ – there’s ‘apparently a clear dispute’ that justifies Court intervention!

Innocent until found ‘plausible’

But is the Convention even applicable in this case? The Court does not know – it hasn’t even begun to judge the merits of the claim. This ruling isn’t about whether Israel committed genocide – it’s about ‘provisional measures’ to be ordered in the meantime. It’s not even about ‘potentially’ – it’s about ‘plausibly’.

‘Plausible’ is such a great word! Not even dictionaries agree what it really means. Cambridge interprets it as

“seeming likely to be true, or able to be believed.”

while Merriam-Webster says it means

“superficially fair, reasonable, or valuable but often deceptively so.”

The two are apparently different, but to the Court one thing is clear: in the world of mere ‘plausibility’, there’s no need for evidence:

“30. At the present stage of the proceedings, the Court is not required to ascertain whether any violations of Israel’s obligations under the Genocide Convention have occurred. Such a finding could be made by the Court only at the stage of the examination of the merits of the present case. . . [A]t the stage of . . . provisional measures, the Court’s task is to establish whether the acts and omissions complained of by the applicant appear to be capable of falling within the provisions of the Genocide Convention.”

So there you are: if I say that Doritos are a choking hazard, this is enough to take Doritos off the market if, in the learned opinion of the Court, the allegations “appear to be capable of falling within” the provisions of food safety legislation.

But what’s all this to do with South Africa, anyway? South Africa isn’t ‘at risk’ of genocide at the hands of those horrible Israelis – not even on ‘Planet Plausible’. So what gives South Africa the right to sue or – in legal terms – what is South Africa’s ‘standing’? I may be really disgusted by Donald Trump’s behaviour; but I cannot sue him for defaming E Jean Carroll. He defamed, not me – so I have no ‘standing’. Why does South Africa?

The Court ruled that, as an international treaty, the Convention is a form of contract, with any country that agreed to be bound by it a ‘party’ to the contract. And so,

“any State party to the Genocide Convention may invoke the responsibility of another State party, including through the institution of proceedings before the Court…”

There you are, problem solved. Anyone can sue anyone. There are 152 such ‘parties’ to the Convention – each of them able to bring any of the other 151 before the Court! In total (use this calculator if you don’t believe me) a possible 11,476 lawsuits.

But, even after granting South Africa ‘standing’, the Court is still left with a major issue: is it even remotely conceivable that Gaza may be subjected to ‘genocide’? Either ‘clearly’, or ‘apparently’ – or both? Even on ‘Planet Plausible’?

‘Just’ killing people – whether combatants or innocents, whether lawfully or criminally – isn’t genocide. Otherwise every war would be a ‘genocide’.

Here the box-ticking exercise begins. The Convention defines ‘genocide’ as

“any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group”.

Are Palestinians “a national, ethnical, racial or religious group”? That in itself could be the subject of nine years of debate. ‘Luckily’, we are still on ‘Planet Plausible’, where no evidence is required – it’s all about appearance:

“45. The Palestinians appear to constitute a distinct ‘national, ethnical, racial or religious group’, and hence a protected group…”

But why does the Convention say “in whole or in part”? Isn’t genocide (as the name implies) an attempt to destroy the entire group? Well, perhaps those who wrote the Convention wanted to prevent ‘defences’ like ‘but I don’t want to kill all the Jews, Your Honour! Just the Zionists…’ I’m just speculating here!

Still: in previous debates, the Court has already established that wanting to kill just a few people isn’t genocide. It has to be ‘substantial’ (whatever that means):

“[T]he intent must be to destroy at least a substantial part of the particular group”.

So how many Gazans were killed? Again, we don’t need evidence – we just need ‘information,’ whether verified or not:

“While figures relating to the Gaza Strip cannot be independently verified, recent information indicates that 25,700 Palestinians have been killed, over 63,000 injuries have been reported, over 360,000 housing units have been destroyed or partially damaged and approximately 1.7 million persons have been internally displaced…”

The Court rather deceitfully attributes the “recent information” to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). But, of course, OCHA was merely quoting the ‘health ministry’ run by Hamas. No matter – OCHA found Hamas data ‘plausible’ and the Court of course believes OCHA. After all, the ‘International Court of Justice’, isn’t really a court and has little to do with justice; it is, just like OCHA, an organ of the United Nations. Part and parcel of its structure and mechanisms. One hand washes the other…

In the process, some of the judges demonstrate not just bias and partiality, but also superficiality and contempt for the facts. In his Declaration (appended to the Court’s ruling), Judge Bhandari writes, inter alia:

“To date, however, more than 25,000 civilians in Gaza have reportedly lost their lives as a result of Israel’s military campaign…”

Of course, nobody – not even Hamas – claims that “more than 25,000 civilians” have been killed. That would imply that the IDF failed to kill even one Hamas combatant. (They must be fighting shadows in Gaza!) In fact, the numbers published by the Hamas-run health ministry in Gaza do not differentiate at all between civilians and combatants – but refer only to the gender and age group (adults or ‘children’) of the victims. (I placed scare quotes around ‘children’, because Hamas’s definition of the term – below the age of 18 – does not unfortunately reflect the organisation’s recruiting practices. There are ‘reportedly’ plenty of 16 and 17 year olds in the ranks of the jidadists).

“[M]ore than 25,000” was, at that time, the total number of Gazan fatalities –civilians and combatants – as alleged by Hamas. That a judge sitting on the high and mighty International Court of Justice – no less – and deliberating on such grave allegations could get such a basic fact wrong is shocking. And who knows how many other judges – who did not bother to append a separate Declaration – are equally poorly seized of the facts?

But even such egregious blunders are irrelevant in the big scheme of things. Because, even if one were to accept at face value the numbers provided by Hamas, it would still be difficult – even for a UN agency – to claim that killing 25,700 people (out of a self-assessed 14.5 million Palestinians) is consistent with “intent . . . to destroy at least a substantial part of the particular group”. That’s why the Court resorts to a sleight of hand: It observes that

“according to United Nations sources, the Palestinian population of the Gaza Strip comprises over 2 million people. Palestinians in the Gaza Strip form a substantial part of the protected group.”

They do indeed. And if the Israelis were intending to kill all 2 million of them, that would constitute a ‘plausible’ suspicion of genocide. But do they?

Intent is essential when it comes to genocide. In World War II, the Allies killed at least 5 million Germans, including circa 500,000 civilians killed by British and American airstrikes. The Soviets worked to death another 500,000. But, however “significant” those numbers were, this wasn’t genocide: what the Allies wanted was to win the war and remove the Nazis from power – not to destroy the German people as such.

In his Separate Opinion, Israeli judge Aharon Barak reminded the Court,

“[t]he drafters of the Genocide Convention clarified in their discussions that

‘[t]he infliction of losses, even heavy losses, on the civilian population in the course of operations of war, does not as a rule constitute genocide. In modern war belligerents normally destroy factories, means of communication, public buildings, etc. and the civilian population inevitably suffers more or less severe losses. It would of course be desirable to limit such losses. Various measures might be taken to achieve this end, but this question belongs to the field of the regulation of the conditions of war and not to that of genocide.’”

In other words, the number of casualties is rather irrelevant to the genocide/not genocide debate. It is the intent that matters.

Twisting words to twist minds

In order to establish ‘plausible’ intent, the Court provided 3 quotes taken from public pronouncements by Israeli politicians. But it did so only after quoting the head of UNRWA, who complained of “dehumanizing language” – as if worried that, without the prior warning, people might not recognise that language as “dehumanising”. In passing, let us note that the head of UNRWA never accused Hamas of dehumanising and genocidal discourse, despite their Covenant overtly calling to the killing of all Jews!

|

| Head of UNRWA, Philippe Lazzarini |

But once again: ICJ is just another UN agency – and so is UNRWA. The head of the latter is, apparently, infallible in the eyes of the ICJ judges – just like the Pope in the eyes of devoted Catholics.

Later in its ruling, using yet another sleight of hand, the Court refers to “direct and public incitement to commit genocide in relation to members of the Palestinian group in the Gaza Strip”. This is merely a quote from the Convention (Article III) – but many will interpret those terms as referring to the same Israeli statements, previously referred to as ‘just’ “dehumanising”.

All three quotes, by the way, are from the days immediately following the 7 October massacre perpetrated by Hamas, so they are suffused with shock and anger. The first (by Israeli Defence Minister Yoav Gallant) was uttered on 10 October. Here is the English transcript, as reproduced by the Court:

“I have released all restraints . . . You saw what we are fighting against. We are fighting human animals. This is the ISIS of Gaza. This is what we are fighting against . . . Gaza won’t return to what it was before. There will be no Hamas. We will eliminate everything. If it doesn’t take one day, it will take a week, it will take weeks or even months, we will reach all places.”

“[H]uman animals” may sound like dehumanising language. But there is zero evidence that Gallant was referring to “a national, ethnical, racial or religious group”. Quite the opposite: the comparison he makes is with ISIS – a terrorist organisation; emphatically not a protected group. He describes the mission as fighting against “the ISIS of Gaza” – a phrase used extensively in Israel to refer to Hamas (including the oft-used hashtag #HamasIsISIS). In describing Gaza after the Israeli operation, Gallant says “There will be no Hamas”, not ‘there will be no Palestinians’. So how exactly – even on Planet Plausible – is this “direct and public incitement to commit genocide”?

Israel’s leftist President Yitzhak Herzog is also quoted as saying, on 13 October:

“We are working, operating militarily according to rules of international law. Unequivocally. It is an entire nation out there that is responsible. It is not true this rhetoric about civilians not aware, not involved. It is absolutely not true. They could have risen up. They could have fought against that evil regime which took over Gaza in a coup d’état. But we are at war. We are at war. We are at war. We are defending our homes. We are protecting our homes. That’s the truth. And when a nation protects its home, it fights. And we will fight until we’ll break their backbone.”

Since the “rules of international law” prohibit the targeting of uninvolved civilians (not to mention genocide!), Mr. Herzog’s expressed commitment to those rules seems to preclude the notion of genocidal intent. True, the Israeli President opines that ”an entire [Palestinian] nation . . . is responsible”. But is that really a call to commit genocide? Many people claim that the entire German people bore some level of collective responsibility (Kollektivschuld) for the Shoah; that they largely accepted – if not actively supported – Adolf Hitler and the Nazi regime; that they followed orders rather than standing up for basic morality; that they were aware of the genocide and yet remained largely silent. All that does not mean that random Germans can be killed, let alone that the German people should be destroyed as such. Assigning moral (or even legal) responsibility is one thing; inciting genocide is quite another. As for “breaking their backbone”, who says that refers to “an entire nation” rather than to “that evil regime”, i.e. Hamas?

The ICJ quote leaves out other comments that Mr. Herzog made with the same occasion. Here’s ITV’s International Affairs Editor Rageh Omar, reporting on that press conference:

“’… until we break their backbone.’

He [President Herzog] acknowledged that many Gazans had nothing to do with Hamas but was adamant that others did.

‘I agree there are many innocent Palestinians who don't agree with this, but if you have a missile in your goddamn kitchen and you want to shoot it at me, am I allowed to defend myself. We have to defend ourselves, we have the full right to do so.’"

So Mr. Herzog makes a clear distinction between “many innocent Palestinians” and those who store and launch missiles. The right of self-defence is invoked only against the latter group. Hardly “direct and public incitement to commit genocide”. Or even “dehumanizing language”!

Finally, the ICJ ruling quotes a tweet by Israel Katz, currently Israel’s Minister of Foreign Affairs. On 13 October 2023, when he was Minister of Energy and Infrastructure, Mr. Katz posted:

“We will fight the terrorist organization Hamas and destroy it. All the civilian population in [G]aza is ordered to leave immediately. We will win. They will not receive a drop of water or a single battery until they leave the world.”

Mr. Katz also draws a clear distinction between “the terrorist organization Hamas” and “the civilian population in [G]aza”. Only the former is to be destroyed, while the latter is ordered to get out of the way. It is pretty clear that the “they” who are supposed to “leave the world” are Hamas – otherwise why make the distinction at all?

If that’s the ‘best’ that can be found as evidence of “direct and public incitement to commit genocide” by Israeli leaders, it decidedly represents slim pickings.

And why would the Court ignore the many statements by Israeli leaders making it clear that the target is Hamas, not the population of Gaza as such? Here’s a selection of such statements – but there are many similar ones.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, on 16 November 2023:

"Any civilian death is a tragedy . . . we're doing everything we can to get the civilians out of harm's way . . . we'll try to finish that job with minimal civilian casualties. That's what we're trying to do: minimal civilian casualties.”

Defence Minister Yoav Gallant, 29 October 2023:

“We are not fighting the Palestinian multitude and the Palestinian people in Gaza.”

Defence Minister Yoav Gallant, on 18 December 2023:

“[O]ur war against Hamas, the Hamas terrorist organization, is a war — it’s not a war against the people of Gaza. We are fighting a brutal enemy that hides behind civilians.”

President Yitzhak Herzog, on 19 December 2023:

“One thing is clear: The people of Gaza are not our enemy. The enemy is only Hamas. And we’re fighting Hamas and its partners.”

Minister Israel Katz tweeted on 14 October (in Hebrew, translation mine):

“The purpose of the movement [of civilians] southwards is to prevent the Hamas murderers from using the population as human shields, to save lives and to remove the threat posed by those Nazis.”

Words can be twisted, statements can be taken out of context, ill-intentions can – if someone is so inclined – be inferred from imprecise language. But real incitement? Here’s an example of “dehumanising language” and of genuine “direct and public incitement to commit genocide”:

“For us, this [the ‘Jewish problem’] is not a problem you can turn a blind eye to-one to be solved by small concessions. For us, it is a problem of whether our nation can ever recover its health, whether the Jewish spirit can ever really be eradicated. Don't be misled into thinking you can fight a disease without killing the carrier, without destroying the bacillus. Don't think you can fight racial tuberculosis without taking care to rid the nation of the carrier of that racial tuberculosis. This Jewish contamination will not subside, this poisoning of the nation will not end, until the carrier himself, the Jew, has been banished from our midst.”

Taken verbatim from a speech given by Adolf Hitler in 1920, this is a very relevant example. Not because Israeli leaders should ever be compared to the Nazis, but because this is the type of statement that the authors of the Genocide Convention had in mind when, shortly after the end of World War II, they wanted to prohibit “direct and public incitement to commit genocide”.

Perhaps sensing that the evidence of “incitement” is embarrassingly thin, the judges resorted to quoting ‘witnesses’:

“53. The Court also takes note of a press release of 16 November 2023, issued by 37 Special Rapporteurs, Independent Experts and members of Working Groups part of the Special Procedures of the United Nations Human Rights Council, in which they voiced alarm over ‘discernibly genocidal and dehumanising rhetoric coming from senior Israeli government officials’. In addition, on 27 October 2023, the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination observed that it was ‘[h]ighly concerned about the sharp increase in racist hate speech and dehumanization directed at Palestinians since 7 October’.”

The problem is that these are not witnesses – they are UN employees with a long history of anti-Israel bias. But even ignoring that bias, it beggars belief that judges would quote non-specific hearsay as ‘evidence’ (however ‘prima faciae’). If ‘s/he said, they said’ were taken to represent evidence, we would all be criminals on our way to prison!

No wonder that Israeli Judge Aharon Barak – himself a stickler for ‘the Law’ above all else – said that the Court’s ruling was based on “scant evidence”.

Ugandan Judge Sebutinde stated that “there are . . . no indicators of incitement to commit genocide”.

Even the German Judge Nolte (who voted in favour of the ruling) was forced to admit that South Africa had not “plausibly shown . . . genocidal intent.”

We’ve no idea what you’re doing – but make sure you don’t!

And yet it’s based on such flimsy non-evidence that the Court decided that the ‘risk of genocide’ to Palestinians in Gaza was ‘plausible’ enough to warrant ‘provisional measures’.

On the other hand, the Court did refuse to order Israel to cease its military operations in Gaza. Now, this is interesting. Not only did South Africa request such an order (it was first and foremost among its demands); but also the Court acted in contradiction with its own very recent precedent: on 16 March 2022, it ordered Russia to “immediately suspend the military operations . . . in the territory of Ukraine”.

So if the Court truly believed that the Jewish state was harbouring ‘plausible intent’ to commit genocide in Gaza, how come it allowed it to continue its military operations in that territory? If I genuinely suspected that they are a choking hazard, why on earth would I allow Doritos to continue to be manufactured and sold?

But, of course, the judges don’t really believe that South Africa’s claims have any merit. They are just going through the motions, immersed in their ‘learned’ box-ticking exercise and practising the suspension of common sense. This was, after all, just a ruling on ‘provisional measures’ with no bearing on the final verdict… In the mind-boggling words of Judge Nolte:

“Even though I do not find it plausible that the [Israeli] military operation is being conducted with genocidal intent, I voted in favour of the measures indicated by the Court.”

Read: ‘even though there’s no Israeli genocide, I voted to protect the Gazans from the Israeli genocide…’

But what ‘provisional measures’ did the Court indicate? Besides the request to impose a cessation of Israel’s military operations, South Africa requested the Court to order as follows:

“The Republic of South Africa and the State of Israel shall each, in accordance with their obligations under the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, in relation to the Palestinian people, take all reasonable measures within their power to prevent genocide.”

This was a bridge too far even for this court: as proposed, the text would conceivably have given the South Africa an excuse (or even a licence) to intervene militarily in Gaza, in order “to prevent genocide”!

Instead, the ICJ ordered

“[t]he State of Israel . . . [to] take all measures within its power to prevent the commission of all acts within the scope of Article II of this [Genocide] Convention”

There are almost as many absurdities as there are words in the sentence above.

Firstly, the order is addressed to “[t]he State of Israel”. But states (or nations) are abstract constructs. States don’t make decisions – governments and leaders do. Quite obviously, states as such cannot harbour intent, such as “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group”.

And what the hell does it mean to “take all measures within its power to prevent the commission” of genocide? As we have seen from the definition included in the Convention, genocides don’t just ‘happen’, they are perpetrated. Killing people – even killing a lot of people – isn’t genocide, unless the killing is perpetrated with a particular intent. Either the government of the State of Israel harbours such intent (in which case it should be ordered to abandon it or not to implement it in practice), or it doesn’t – in which case whom and how is it supposed to “prevent”? Indeed, given the way in which the ICJ order is worded, the Israeli government might interpret it as an injunction to continue to fight Hamas, in order to prevent that terror organisation from committing “all acts within the scope of Article II of this [Genocide] Convention”.

But what if we interpret the order as saying (albeit in an exceedingly vague, convoluted and imprecise manner) ‘Government of Israel, you are hereby ordered not to commit genocide in Gaza’? Put like this, such order may sound quite stern; but it goes no farther than the legal obligations that Israel had anyway – prior to and independent of the ICJ order; obligations that Israeli leaders do not contest at all.

As Judge Sebutinde wrote:

“In my view, the First [provisional] measure obligating Israel to ‘take all measures within its power . . .’ effectively mirrors the obligation already incumbent upon Israel . . . and is therefore redundant.”

In fact, 5 out of the 6 ‘provisional measures’ prescribed by the ICJ fall in the same category of redundant injunctions: they ‘order’ Israel to do what it is in any case legally obliged to do. That’s like issuing a court order to the Doritos supplier to ‘take all measures within its power to prevent the sale of products that contravene the Food Safety Bill’.

Ordering the unreasonable

But there’s more: extreme as it was, the South African proposal referred to “all reasonable measures within their power”. In its lack of wisdom, the ICJ decided to do one better: the judges took away the term “reasonable” and left just “all measures within its power”. This enables someone to argue that Israel must do absolutely everything in its power – however extreme, disproportionate and unreasonable.

Say Hamas were shooting rockets into Israel from within a residential building; Israel would presumably have to send its soldiers on a bayonet charge in order to remove the threat. After all, a bayonet charge is definitely “within its power”, while bombing the building risks

“(a) killing members of the group,”

something that Israel has been ordered not to do. But even a bayonet charge may not satisfy the judges, as it won’t completely eliminate that risk – let alone the risk of

“(b) causing serious bodily or mental harm to the members of the group;”

So perhaps Israel is obliged to do nothing at all in such a case. Doing nothing is, arguably, “within its power” and presents no risk of genocide. Well, not against the Palestinians, anyway!

Three of the ICJ judges are native English speakers. Don’t they understand that the antonym of ‘reasonable’ is… ‘unreasonable’??

As for the 6th ‘provisional measure’ (the only one that isn’t superfluous by definition), the Court ordered Israel to

“submit a report to the Court on all measures taken to give effect to this Order”.

And to do so “within one month” (rather than within one week, as South Africa requested).

We know what the Court intends to do with that report:

“The report so provided shall then be communicated to South Africa, which shall be given the opportunity to submit to the Court its comments thereon.”

But we also know (and so should the Court) what South Africa’s comments will be. After all, South Africa wanted the ICJ to order Israel to “immediately suspend its military operations in and against Gaza”. So, unless Israel offered to do exactly that (despite not having been ordered to), South Africa will surely argue that Israel’s “measures” are insufficient – that they do not completely “prevent” genocide. And how exactly will the Court assess what really is “all measures within its power” etc. etc. – and what isn’t? Will the Court (which lacks any military expertise) end up dictating specifically what should be done in the field and how – and thus in effect put itself in charge of IDF operations? Even more importantly: exactly how is all this relevant to the issue of intent – which is the crux of the matter when it comes to genocide?

Some – including Israelis and Diaspora Jews – have tried to find consolation in the following paragraph of the ICJ ruling:

“85. The Court deems it necessary to emphasize that all parties to the conflict in the Gaza Strip are bound by international humanitarian law. It is gravely concerned about the fate of the hostages abducted during the attack in Israel on 7 October 2023 and held since then by Hamas and other armed groups, and calls for their immediate and unconditional release.”

In my opinion, rather than improving, this paragraph makes the ruling – if it were possible – even more outrageous.

The paragraph has no place in a case of genocide – it is a transparent political attempt to ‘demonstrate’ even-handedness. To ‘call’ for the release of hostages is the language of empty diplomacy, not of law. If the Court wanted to deliver a meaningful gesture, then it should have joined Judge Sebutinde, who remarked, with thin irony:

“In its Request for provisional measures, South Africa emphasised that both Parties to these proceedings have a duty to act in accordance with their obligations under the Genocide Convention . . . leaving one wondering what positive contribution the Applicant could make towards defusing the ongoing conflict there. During the oral proceedings in the present case, it was brought to the attention of the Court that South Africa, and in particular certain organs of government, have enjoyed and continue to enjoy a cordial relationship with the leadership of Hamas. If that is the case, then one would encourage South Africa as a party to these proceedings and to the Genocide Convention, to use whatever influence they might wield, to try and persuade Hamas to immediately and unconditionally release the remaining hostages, as a good will gesture. I have no doubt that such a gesture of good will would go a very long way in defusing the current conflict in Gaza.”

I would add (with plenty of Zionist irony and zero expectations) that the UN, including the ICJ, views Gaza as part of the State of Palestine. So – having expressed ‘grave concern’ for the Israeli hostages – shouldn’t the Court order the State of Palestine to “take all measures in its power” to bring about their release? For starters, how about indicting the leaders of Hamas for an obvious war crime perpetrated – in theory at least – under the jurisdiction of the State of Palestine?

Stupidity has consequences

So let me summarise: the International Court of Justice’s failure to recognise South Africa’s application as vexatious, politically motivated and fundamentally without merits will ensure that this ‘legal’ circus will now perform for years, abusing public money, misusing resources, poisoning international relations and distracting attention from genuine issues.

The ‘provisional measures’ ordered by the Court are not just unnecessary, but pointless and irrational.

Unfortunately, however, this is not all. By their failure to apply common sense, their blind dive into legalistic detail at the expense of assessing the bigger picture and (in some cases at least) their lack of integrity, the judges have produced a series of severely deleterious consequences. I will analyse some of them below – not necessarily in the order of gravity.

Firstly, this harms the reputation of the Court – such as it is. The ICJ has no enforcement power (both USA and Russia have already treated its rulings with contempt) and relies entirely on reputation to lend it any sort of influence.

Secondly (and more importantly), by ‘playing along’ with South Africa’s charade, the judges trivialised the notion of genocide (aptly called ‘crime of crimes’) and made a mockery of one of the most important international agreements arising from the inferno of World War II. Their ruling –now elevated to the rank of ‘existing jurisprudence’ – guarantees that the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide and similar agreements will increasingly be abused. They will more and more become political tools, instruments of ‘lawfare’, additional ways for dictators, corrupt governments and rogue regimes to harass other nations. Expect an inflation of ‘genocides’ and other specious accusations that (since the Court has set the bar of ‘plausibility’ so low) will now have to be examined and will produce a flurry of devalued ‘provisional measures’ and ‘rulings’ that – increasingly – nobody will give a damn about.

Thirdly, such frivolous ‘judicial’ process will surely discourage states from joining the Genocide Convention – and other international instruments. Currently, 153 states are members of the Convention, while 41 UN members states are not. But among the member states, many (including USA, Russia and China) have joined with reservations and objections. Many of these reservations (including one submitted by USA) deny ICJ jurisdiction – unless expressly accepted by the member state in question. Israel signed the Convention (with no reservations) in August 1949 – almost immediately after the end of its War of Independence and much earlier than the UK (1970) and USA (1988). But knowing what they know now, what conceivable Israeli government would voluntarily put itself under ICJ jurisdiction? Would Israel (and other countries) sign existing and future treaties, knowing that they can be used maliciously, to ‘legally’ harass them?

Fourthly, far from bringing about peace and understanding, accepting such tendentious claims serves only to sow discord among states and nations. The ICJ procedure allows states to ‘intervene’ in favour of one side or the other – which of course results in the creation of acrimonious, bitterly opposed ‘coalitions’. In one case, no less than 32 different countries ‘intervened’ in such a dispute. More worryingly, this is likely to make peace between Israelis and Palestinians even more unlikely. As Judge Sebutinde opined, “the dispute between the State of Israel and the people of Palestine is essentially and historically a political one, calling for a diplomatic or negotiated settlement” – rather than a legal dispute to be resolved in court. We are looking now at years of litigation, during which the Palestinian leadership would pretend at least to believe Israel guilty of genocide. How is that leadership then expected to ‘sell’ to their own people making concessions to ‘perpetrators of genocide’?

From ‘never again’ to ‘again and again’

But I left the saddest and most upsetting consequence for last. Think about it: why genocide? This is a rarely used accusation. In fact, in 75 years the Convention has only been legally invoked only twice before:

- In 1993, Bosnia-Herzegovina sued Yugoslavia for alleged genocide perpetrated against its Muslim (Bosniak) population. More than 30,000 Bosniak civilians had been killed (out of a population of circa 1.8 million). Bosniaks represented more than 80% of the total number of civilians killed in that war. Yet the ICJ ruled that no genocide had been perpetrated – except in one particular instance: the massacre of Srebrenica.

- In 2019, the African state of Gambia sued Myanmar, alleging that the latter committed genocide against its Muslim Rohingya population. Circa 25,000 had been killed and 750,000 fled to Bangladesh. The case is still being tried.

Needless to say, a lot of other mass atrocities – which many claim were genocide – took place in those 75 year. One can point for instance at Indonesia (1965-1966, at least 500,000 deaths), Bangladesh (1971, at least 300,000), Cambodia (1975-1979, at least 1.5 million), Guatemala (1981-1983, c. 166,000), East Timor (1975-1983, at least 100,000), Rwanda (1994, at least 500,000), Ethiopia (ongoing), Sudan (ongoing), China/Xinjiang (ongoing)…

In the Middle East alone, genocide is alleged to have taken place in that period against Kurds, Marsh Arabs, Christians, Yazidis, Shabaks and Turkmens.

None of those instances (some of which continued for years or are still ongoing) was brought before the ICJ – although some countries ‘recognised’ those atrocities as genocide. So we are entitled to ask – why Israel? What makes the conflict in Gaza (only 100 days after it was started by the rulers of that territory) different? Why is the Jewish state only the 3rd country in 75 years to be formally accused of this ‘crime of crimes’ – and dragged before the international court?

Accusations of war crimes against Israel are not a new thing. Nor are a host of other allegations: massacres, ethnic cleansing, apartheid, land grab, etc. etc. But let’s be clear: genocide is not ‘more of the same’ – it is (or should be) in a category of its own. The most well-known genocide in history is the Shoah – the systematic, industrial-style extermination of the Jewish population of Europe. The term itself was coined by a Jew (Raphael Lemkin) in 1944 – as a generic category for the Shoah, for what Churchill initially called “a crime without a name”.

That, a few decades later, the Jewish state (‘the Jew among nations’) finds itself accused that that exact crime is not by chance; it’s symptomatic.

Israeli psychiatrist Zvi Rex once remarked:

"The Germans will never forgive the Jews for Auschwitz.”

But, of course, it wasn’t just the Germans and not just at Auschwitz. To paraphrase Rex, the world has never forgiven the Jews for the Shoah. It seeks to assuage pangs of conscience by discovering new ‘reasons’ to hate the Jews. German social psychologist Peter Schönbach called this ‘push back’ against feelings of guilt ‘secondary antisemitism’.

Most European and America Jews are shocked by the current ‘sudden eruption’ of antisemitism. They did not personally experience such intense hostility in the past, so they view it as a new phenomenon. But nothing is farther from the truth. Of course, after the Shoah it became less acceptable to manifest overt antisemitism in the street. But antisemitic ideation continued in ‘scholarly’ circles, under the excuse of ‘academic research’ and academic freedom. It grew and fermented in that fertile environment, before first seeping and then bursting out in the open.

The crudest form of secondary antisemitism is Holocaust denial. It is still very much ‘out there’, but more ‘subtle’ varieties have been developed. In both ‘über-progressive’ and far right circles, there is widespread universalisation, trivialisation and banalisation of the Shoah. As early as 1949, German philosopher Martin Heidegger was comparing “the production of corpses in gas chambers and extermination camps” with… modern agriculture.

While such far-fetched ‘metaphors’ may be relatively rare, it has become commonplace to refer to the Shoah as ‘just another’ genocide – and even to imply that it is surpassed in importance by other historic phenomena: the Atlantic slave trade, the colonial oppression, capitalist exploitation, anti-black racism in USA, homo- or transphobia, etc.

Reflecting precisely this tendency, in 2011 Jeremy Corbyn (at the time a Labour Party backbencher, but later elected to lead that party) submitted a proposal to change the name of Holocaust Memorial Day to “Genocide Memorial Day – Never Again For Anyone,” to reflect that “Nazism targeted not only Jewish [people]”.

But the ultimate form of secondary antisemitism is ‘Holocaust inversion’. If one can claim that Jews are now the ones committing genocide – then feelings of guilt are no longer required. Quite the opposite – one can signal one’s virtue by fighting (at no risk to life or limb) against the ‘Zionists’ (portrayed as the new Nazis) and in defence of the Palestinians – the new ‘Jews’.

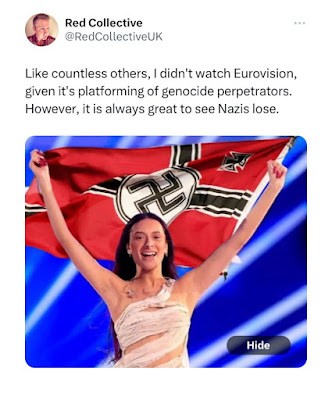

|

| The post above has been 'liked' by almost 10,000 X (formerly Twitter) accounts. |

In hard-left and hard-right circles, accusations of genocide against Israel are nothing new. But South Africa’s ICJ application is meant to give it a ‘seal of approval’ and bring this ‘perfected’ version of secondary antisemitism into the mainstream. In this context, it does not matter if, 5 or 7 years from now, the Court will acquit the Jewish state. No, the damage was done the moment the judges agreed to try the case – the minute they declared that accusation ‘plausible’. Future historians will look at 26 January as a watershed moment.

On the eve of Holocaust Memorial Day, the International Court of Justice legitimised Holocaust inversion. ‘Never again’ was used to promote ‘again and again’.

|

| Ghazi Hamad (a senior leader of Hamas) says that the latter will strike "again and again", until Israel is "removed" |

%20(1).jpg)

- Follow Us on Twitter!

- "Join Us on Facebook!

- RSS

Contact